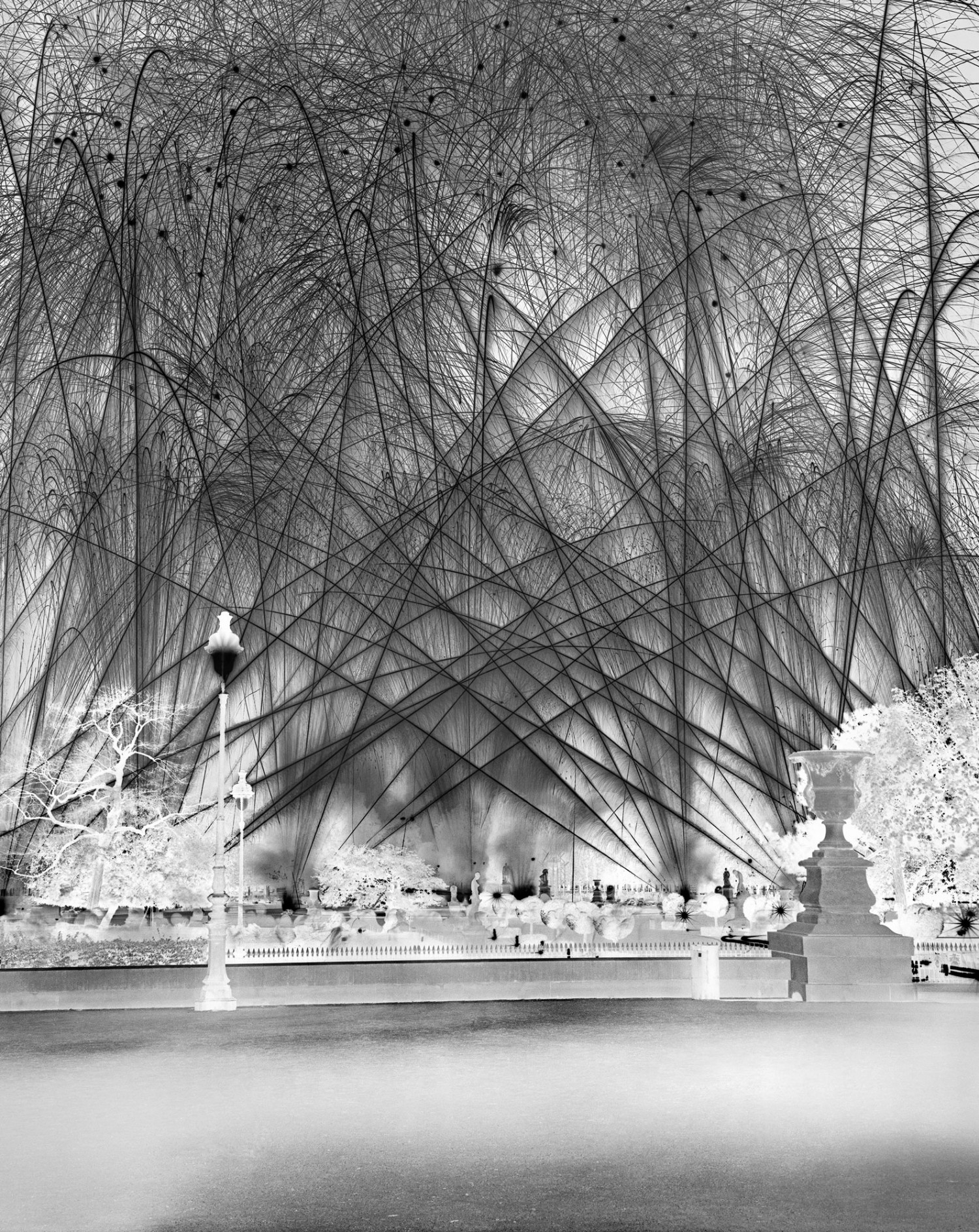

FIAC I, Heckscher Museum of Art, New York

Untitled X (right), The Heckscher Museum of Art, New York

FIAC I, Heckscher Museum of Art, New York

Untitled X, The Heckscher Museum of Art, New York

Lisa Sette Gallery @ AIPAD Photography Fair, New York

Lisa Sette Gallery @ AIPAD Photography Fair, New York

Lisa Sette Gallery @ AIPAD Photography Fair, New York

Lisa Sette Gallery @ AIPAD Photography Fair, New York

Black Powder Installation, Fotofest, Houston

Black Powder Installation, Fotofest, Houston

Black Powder Installation, Fotofest, Houston

Black Powder Installation, Fotofest, Houston

Black Powder Installation, Fotofest, Houston

Black Powder Installation, Fotofest, Houston

Black Powder Installation, Fotofest, Houston

Black Powder Installation, Fotofest, Houston

Black Powder Installation, Fotofest, Houston

Black Powder Installation, Fotofest, Houston

Black Powder Installation, Fotofest, Houston

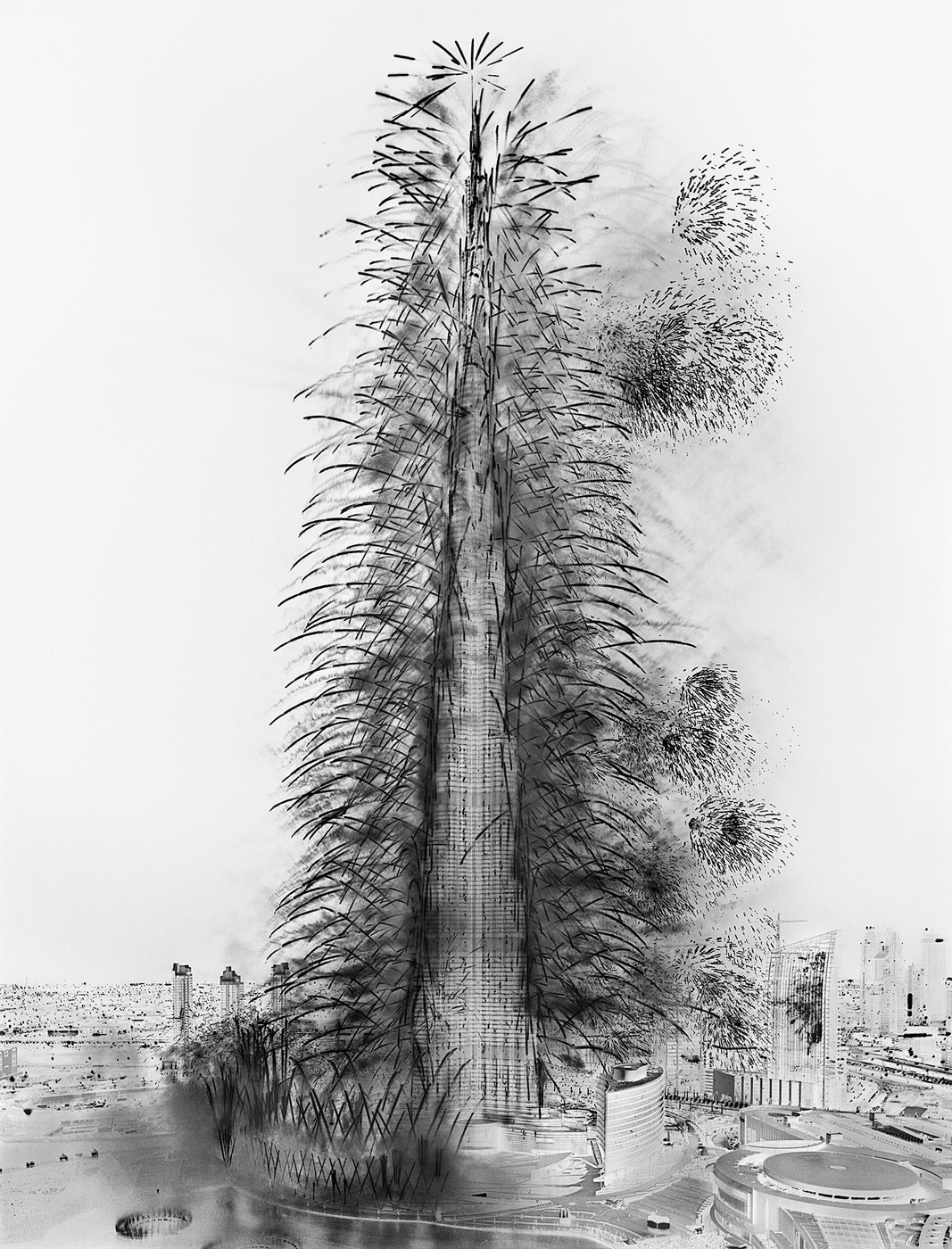

Inauguration, Burj Khalifa, Private Residence, New York

Untitled X, Private Residence, New York

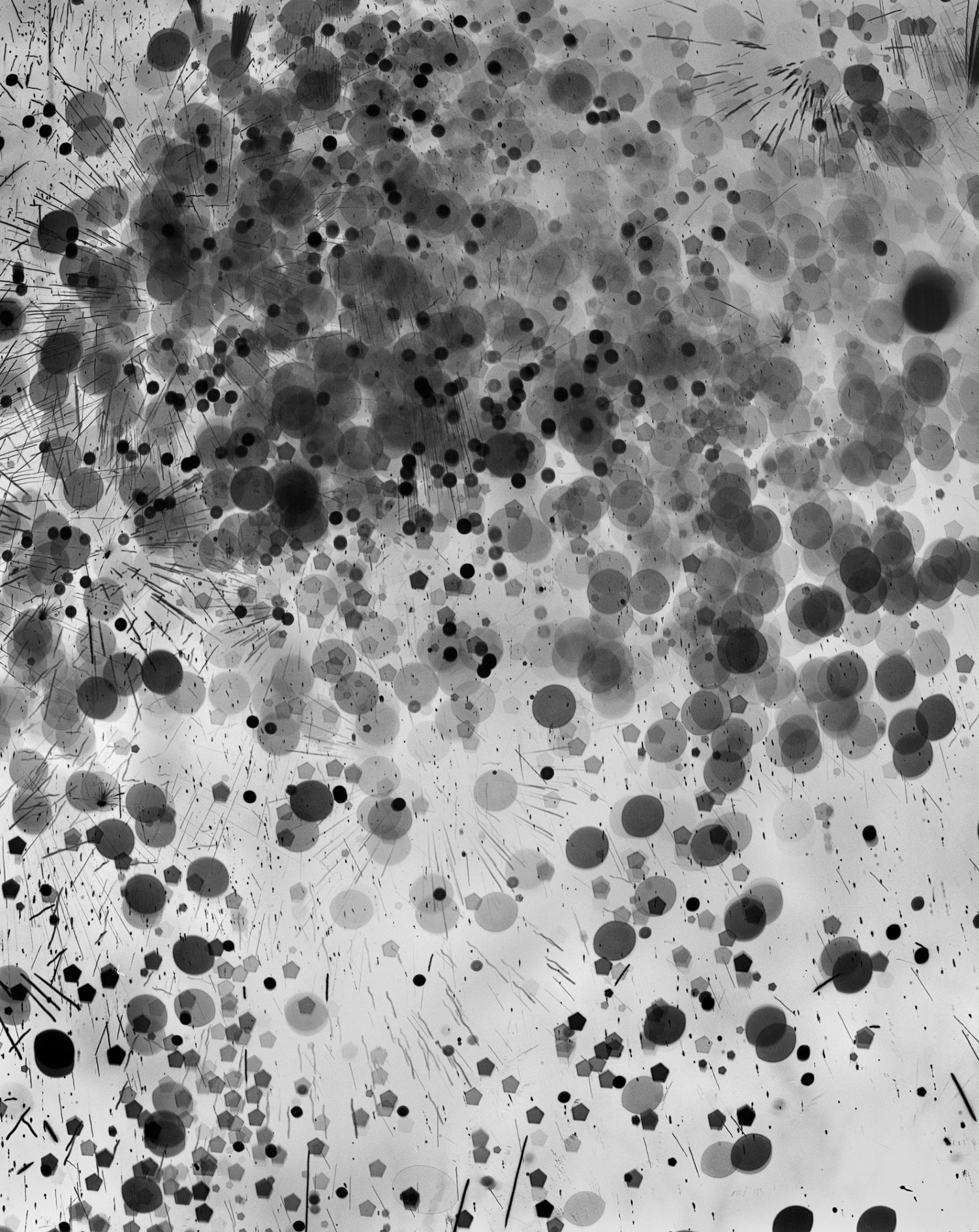

Black Powder

Black powder, also known as gunpowder, was the earliest known chemical explosive. Its discovery in 9th century China was made by Taoist alchemists who inadvertently created it during their quest for an elixir of immortality. The powder was poured into hallowed out bamboo sticks, forming the first man made fireworks, and used to frighten away evil spirits and bring happiness and prosperity.

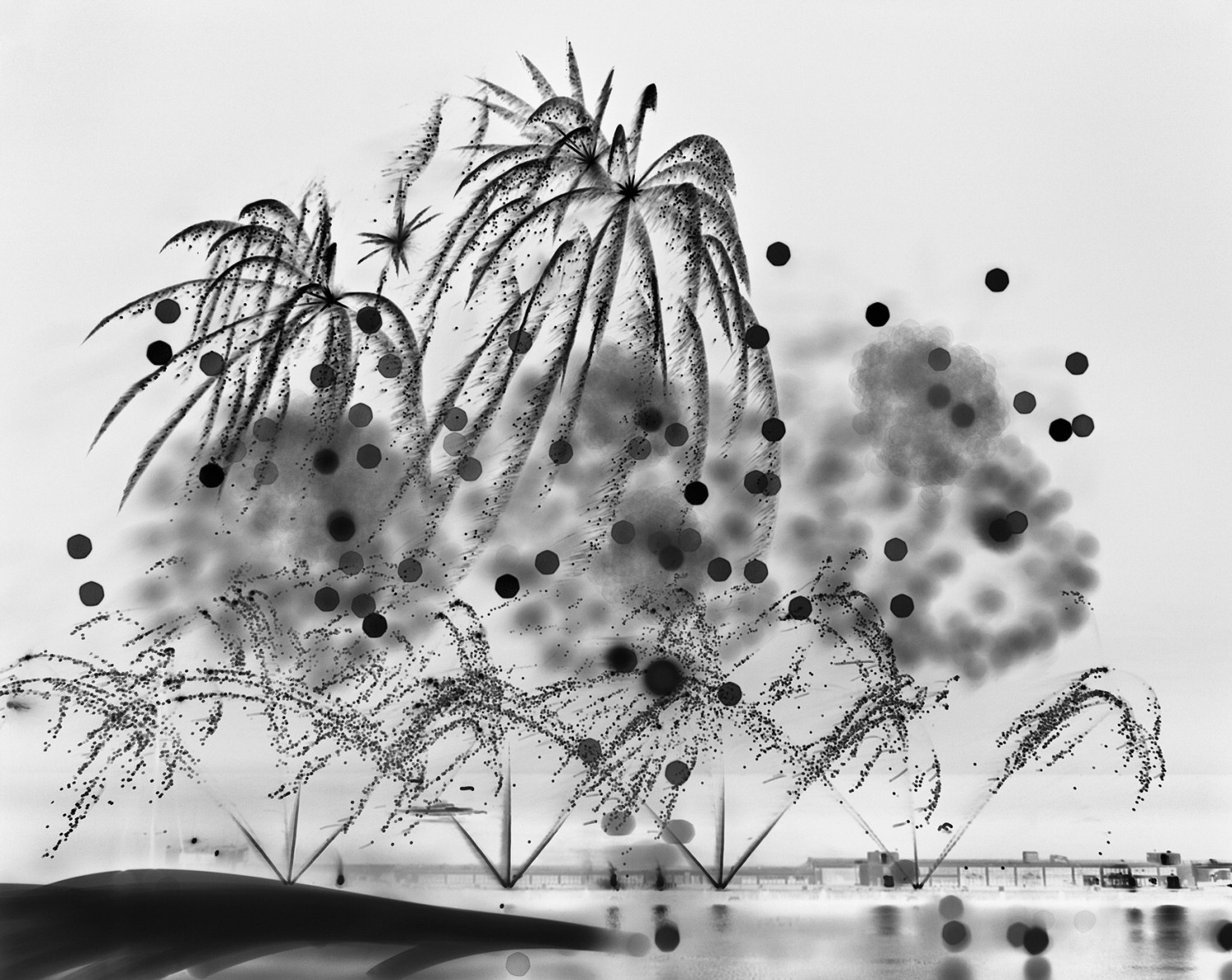

This body of work ostensively documents worldly events memorialized with pyrotechnics, in an attempt to frame the varying roles that fireworks and their derivatives have continually played through history, and think through the ways that spectacle, celebration and capitalism have become almost indistinguishable in the contemporary era.

Working with a large-format film camera, these photographs were made using one or more in-camera techniques, such as long-exposure, multiple-exposure, or unorthodox combinations of focus and aperture, to select, sculpt and multiply the explosions onto a single sheet of film, which is scanned and then printed as a facsimile enlargement of the original negative.

The resulting images endeavour to deconstruct the cliché by reversing the intrinsic hierarchy of the negative-positive process, a technology little changed since Fox-Talbot made his ‘photogenic drawings’ almost two hundred years ago. What is not seen is just as important as what is. What is black is equally important as what is white. The negative image, elevated to function as the definitive work, is grounded in the anomalous and animates an otherwise simple reading that is both transformative and familiar, expanding upon an underlying dialogue with more traditional modes of art-making.

Rocket-propelled explosions of light punctuate the sky in the form of a prismatic blend of inky-black calligraphy, whose overlapping trajectories trace a cacophony of concave and convex arcs, a matrix of forms sharp and blurred, straight and wiggly. While some of these images proffer beguiling beauty, bringing to mind fecund botanical gardens and dense tree canopies, others appear far more troubling, reflecting the unsettling dichotomies that define our time with its ideological eruption of independent terrorism and state-sponsored violence.